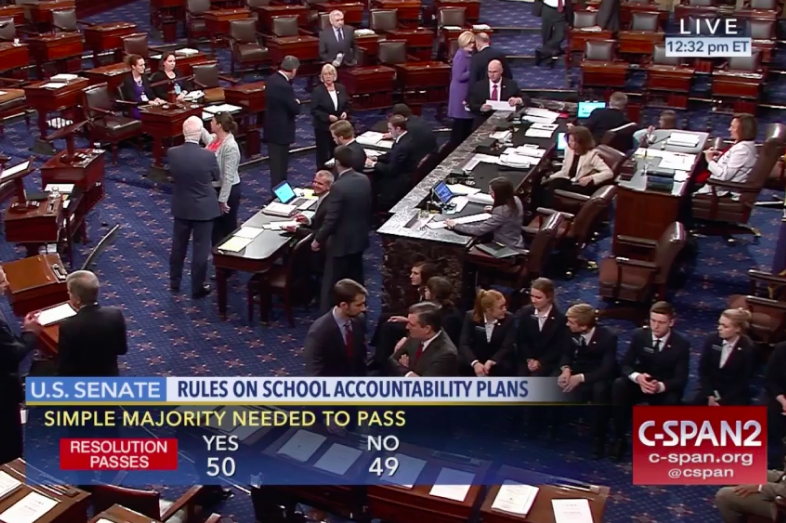

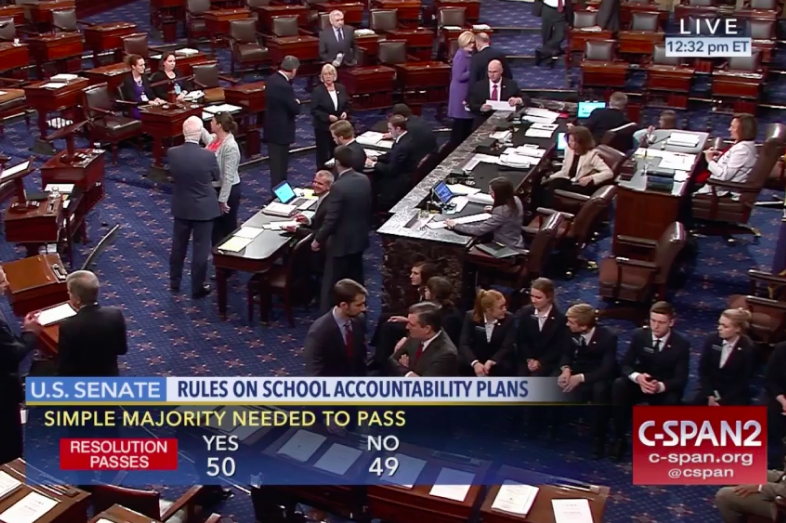

The U.S. Senate, by a 50 to 49 vote yesterday, all but sounded the death knell for Obama administration regulations governing how states must carry out school accountability requirements under federal law. President Donald Trump said he will sign the measure, which was backed by all but one Senate Republican (and earlier won approval in the House).

So, what exactly does this mean for states and schools, and what happens now?

What’s been undone? The Every Student Succeeds Act — the nation’s main federal law for K-12 education – remains in place. (ESSA replaced No Child Left Behind last year — eight years overdue, thanks to historic levels of interparty squabbling over the the broad as well as the fine print.) The overturned regulations set requirements for accountability under ESSA, including what factors could be used to judge school quality, how low-achieving schools would be identified for extra support, and how states should handle circumstances where large numbers of students “opt out” of statewide testing.

As Education Week reported Thursday, “Without the rules, the requirements for accountability and state plans will be found in the language of ESSA itself.” (An earlier story by reporter Alyson Klein walks through in greater detail what ESSA says and what the Obama rules said on key issues.)

The final rules were released by the Obama administration on Nov. 28, several weeks after President Donald Trump won the election.

Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-Tennessee), the chairman of the Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, argued that the regulations went beyond what the law — of which he was a chief architect — prescribed, and tied the hands of local education officials. The powers of the U.S. secretary of education were actually more strictly limited without the regulations, Alexander said. Indeed, the ESSA statute specifically prohibits the secretary from certain actions — a rebuke of what some considered overreach by the Obama administration.

Alexander: The issue before us is whether Congress writes the law or the Department of Education writes the law.

— Lamar Alexander (@SenAlexander) March 9, 2017

But Sen. Patty Murray (D-Washington), the senior Democrat on the Senate education committee, warned that repealing the rules would undermine crucial civil rights protections for students and allow Education Secretary Betsy DeVos to “take advantage of the chaos that will follow.”

We know from experience that w/o strong accountability rules, our most vulnerable students too often fall through the cracks. #ESSA

— Senator Patty Murray (@PattyMurray) March 9, 2017

Civil rights and educational equity advocates say the regulations were needed to keep states in check, and to insure the neediest students aren’t ignored. Among those raising such concerns is the Education Trust, a D.C.-based organization focused on closing the opportunity and achievement gap for underserved students. (It’s newly named president is John King, who served as education secretary in the final year of the Obama administration):

“The Senate’s action to overturn the accountability, state plan, and public reporting regulations was misguided. This resolution will cause unnecessary confusion, disrupting the work in states and wasting time that students — particularly those who are most vulnerable — cannot afford for us to waste.”

On the other hand, some organizations were supportive of the repeal effort, including groups the National Governors Association, and the ASSA – the association representing school superintendents. But even as reporters’ inboxes were filling with statements from groups either “condemning” or “applauding” the vote, the office of Secretary DeVos was surprisingly silent.

This did not go unnoticed, including by education policy analyst Chad Aldeman:

Was it too much to ask @BetsyDeVosED to issue some bland, reassuring statement today after Congress pulled the ESSA regulations?

— Chad Aldeman (@ChadAldeman) March 10, 2017

Was this vote to repeal the regulations a surprise? No. The ESSA accountability rules were on a Republican “hit list” of Obama-era regulations that lawmakers most wanted to repeal. Critics of the Obama rules contended that they restricted states’ authority to hold their own schools accountable — and went against the intent of the bipartisan education law,, which was designed to restore more state and local control.

For his part Michael Petrilli, the president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank, wrote that while he was not in favor of all of the regulations — and if forced to choose between all or nothing, he’d choose nothing — there were a few in the mix worth saving. His picks included letting schools adjust English Language-Learner programs to best meet individual students’ needs, and granting leeway in how test scores for students with disabilities are counted. Some of those rules could be resuscitated in “Dear Colleague” letters from Secretary DeVos. But those missives lack the force of law.

Anne Hyslop, a senior analyst at Chiefs for Change, a network of state and district education leaders, identified 40 ESSA rules that would be undone by the Senate vote. Of those, half actually gave states greater flexibility in key areas, according to Hyslop, who previously worked in the Obama administration. They include: how states set goals for student achievement; how different types of data, such as graduation rates, could be weighted; and how they shared school achievement data with parents and the broader public. Also falling by the wayside? A provision that required schools to use at least one intervention that had a track record of success.

“Taken from us too soon, after a valiant fight with “local control.” https://t.co/T2NvIzbBwc

— Morgan Polikoff (@mpolikoff) March 9, 2017″

What’s next for states? There’s no question the policy reversal will have a trickle-down effect to local schools, adding yet another element of uncertainty to the forecast for the nation’s new era of federal policy for public schools. States still must submit their revised accountability plans for review and sign-off by the U.S. Department of Education. It’s up to DeVos (and the team she’s still assembling) to decide whether those blueprints are rubber-stamped or put through a fine-mesh sieve. At the same time, there’s no reason states can’t hold themselves to an even higher standard than what was laid out in the now-defunct regulations, say Chiefs for Change officials.

Allison Dembeck of the the U.S. Chamber of Commerce told Politico her organization is deeply concerned about the impact. “The final stages of these plans are already in place, so to suddenly pull the rug out from under states and local [school districts], that’s not a good place to be in,” Dembeck said. “At the end of the day, you’re risking delaying implementation of the law and I think it’s really important to remember that there’s kids at the end of this.”

But the state superintendent in Idaho, Republican Jillian Barlow, sees things differently. ESSA is “such a robust and specific law that it doesn’t cause a great deal of consternation without rules and regulations,” she told Emma Brown of The Washington Post. With or without the regulations, Barlow said, Wyoming is “going down the same path.”